Note for readers: The theme of this piece is about the degradation of journalistic standards as a consequence of the surge in self-publication in our industry. In order to demonstrate what’s being lost, I employed one of the UK’s top magazine editors – Anna Leszkiewicz (with whom I happen to co-parent a dog) – to do a quick edit on my piece. I haven’t incorporated her edits, instead I’ve left her annotations in the text, so that readers might see the difference between the piece I wrote and the piece she wishes I had. Where the text is italicised, she has amended my sentence. Where the text is scored through she has removed my words. [Her observations are included, italicised, in square brackets]. As a result of giving Anna my italics, some words that I would normally italicise have, in this piece, been emboldened. This piece has proved quite a lot of faff, so please do consider sharing it.

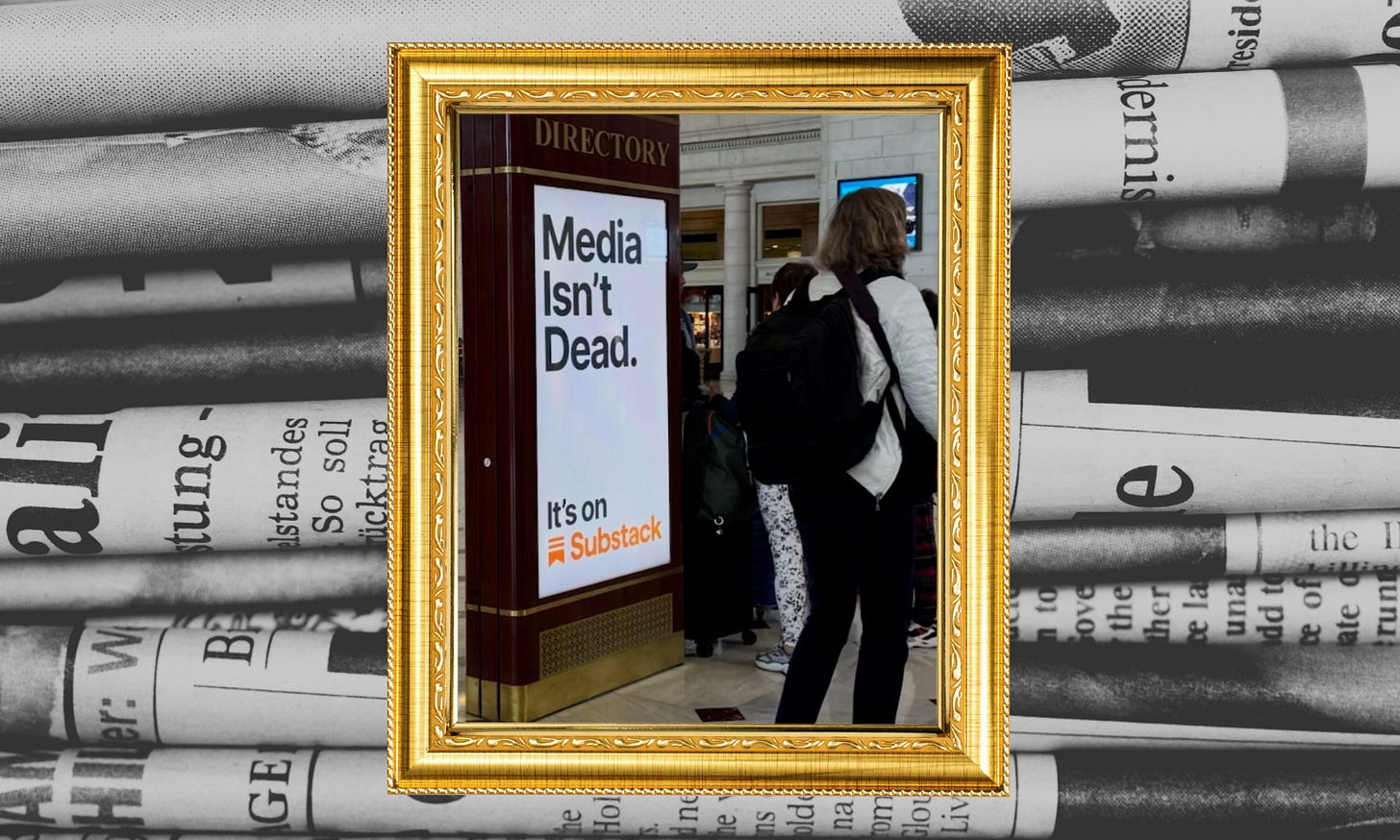

Commuters visiting Grand Central station in April were greeted by a billboard that proudly proclaimeding the slogan: “Media Isn’t Dead. It’s on Substack.” About a kilometre, as the crow flies, from the New York Times building, it felt like a provocation. ‘You think the media is dead’, it announced, ‘because you are looking in the wrong places’. Those wrong places include, it would seem, legacy media, which is, in fact, dead. [Something a bit tortured here -- is media the thing being looked for? Or is it the place something is being looked for in?]

Of course, whether it’s on Substack or in the storied pages of the Times [cut?], the media isn’t dead. It’s in a constant state of evolution, and right now there seems to be a concerted move towards self-publishing. A couple of decades ago, “self-published” was a dirty word, conjuring up images of vanity presses and writers who couldn’t get anyone to distribute their work. Then the internet era came along and blogging – briefly – became du jour [Think you'd usually say "became the x du jour" but I'd lose the cliche altogether] amongst aspirant hacks. But like all great revolutions – from the Protestant reformation to BritPop – it was followed, rapidly, by a counter-revolution. Curation reasserted itself; prestige publications provided guardrails against the unfiltered bilge of the web. The current moved back towards the mainstream. [Something of the mixed metaphor here with guardrails/bilge/current/mainstream etc? I suppose a guardrail can stop you falling into water but still feels like too much going to me, don't think they all go with each other.’]

But in the background a push and pull persisted, establishing a creative tension within the media. Streaming Video streaming, for example, spawned unprecedented budgets and audiences, yet, at the same time, YouTube was creating the greatest democratisation in video content [v personal and subjective but I think the word "content" is really corporate and horrible and prefer not to use it uncritically?] since Louis Le Prince filmed his in-laws in his back garden yard. Now, prestige TV is prestigier* than ever, yet audiences are ever more likely to opt, instead, for content created outside any sort of studio system. It is a content arms race that mirrors, in some ways, the dot-com bubble itself, where good money was chasing bad into online businesses. [Arms race, mirror, bubble, chase... Too many metaphors/cliches in one sentence, quite aside from the question of style, it becomes hard to parse?] And journalism has been no exception: a few bloggers started making half-decent money which precipitated a flood of cash into the medium, the rapid professionalisation of writing for the web, and then its eventual implosion. Whether the same ruin awaits streamed video remains to be seen – but right now the journalism sector is witnessing the long tail of bad decisions made at the turn of the millennium.

*[Think you really have to earn a flourish like this. Separately, do you think that its true? That prestige TV is at its most prestige now? I don't..]

At the heart of the issue is a core fault [double cliche/mixed metaphor (a heart doesn't have a fault)]: the over-reliance on advertising when the internet didn’t have mature payment mechanisms [When was this? Think you need more dates and times etc throughout]. This devalued journalism as a product, eroded the public belief that quality content should be paid for, and decimated the revenue models of every media business of that time. (Not to mention killing off print advertising in the process, thanks a lot**). It is a mistake that is particularly hard to row back from [cliche]. It is far easier to ask people to pay for a product they have never tried before, than it is to ask them to start paying for something they have enjoyed, for free, for many years. And so, at the level of turnover required to run a fully-fledged media operation, the counter-reformation, the push to drive paying subscriptions, has been tortuous and arduous. Just look at Press Gazette’s tracker of job cuts in 2025 – it’s a brutal time to be in the press. [Wonder if it's worth here or later making the link between declining standards and cost cutting clearer?]

**[Who is this aimed at?]

But – aha! – remember that the media isn’t dead. It’s just on Substack. Not a day seems to go by without another big shot mainstream [one of these adjectives not both? repetitious] journo upping sticks and moving across to the platform. Founded in 2017 by

And so, we enter the Substack Age – or the Podcast Age or the YouTube Age or the Whatever Age I Like, Really (WAIL,R) – where the medium is diversified, atomised and creator- focused [This phrase gets a yuk from me!]. Journalists are expected to be their own “brands” now, carrying audiences across from columns in dusty old newspapers to digital? newsletters or streaming? shows that bear their names in bright lights. They are performing many different roles: the writer, the editor, the publisher, and the product. Richardson, possibly Substack’s top earner, is reported to employ just two people in her multi-million dollar enterprise, a part-time copy editor and a remote former advertising exec. Other than that, it is a solo effort. And she’s the biggest player in town – Gulliver in Lilliput – and thus probably employing a bigger team than the average convert. Why, when the platform rewards frequency and immediacy, go to the trouble of employing editors who will just slow you down?

“Not having editors is liberating in the same way that running my own bookshop is liberating,” says

, a former Economist journalist who sacked it all in [In a newspaper I'd probably change this to eg "left the industry" but think it's fine to be more colloquial here] to open his own bookshop, Backstory, a journey [transition?] which he has chronicled on his acclaimed Substack. “If I have an idea, I can do it. Right now.”That offers a dual pull [journalese?]. For decades, journalistic standards have included meant that pieces have to endure a fairly rigorous research and fact-checking processes. The New Yorker, for example, is famous for its diligence in this area, double verifying minute details like a subject’s preferred preparation of eggs or the weather on a particular Friday in 1972. And even though this process has diminished been corroded in mainstream journalism (the hundreds of articles I’ve published professionally in the past decade have been regularly strewn with errors), most publications will still insist a piece is read by on at least two editors readers before it any piece goes to press.***

***[Sounds like you're saying most writers would prefer for their piece not to be fact checked? Is that appealing??? I think you need to say this slows things down or something to make clear what the downside would be and why someone might prefer NOT to be fact checked.]

Then there’s the appeal of not needing to pitch the idea in the first place. The second allure of this is born out of the world of pitching. For freelance journalists, pitching [I'd define pitching in brackets or parenthetical dashes here] pieces is incredibly time consuming and demoralising. It was bad enough in a world where pieces were commissioned at a $1.50 [Wondering why this in dollars as I think most of your experience is British?] per word rate; it’s appalling now that half the publications aren’t taking on new freelancers, and the other half are trying to get away with $0.20 a word. New writers, without a public profile, are pitching into the void. It doesn’t really matter how good your idea, how provocative your thesis, how elegant your writing is – you’re probably going to get ignored.

“A personal brand always makes things easier,” says Lex Roman, author of Journalists Pay Themselves, a newsletter about… how journalists getting paid. “Especially in the era of AI, physically standing behind your work goes a long way towards getting readers to trust and pay you.” It’s a little stomach-churning kind of a sickener, then, to know that the same few people who are still getting lucrative newspaper or magazine commissions, are the same few people who are also able to generate revenue on Substack. Just look at the solo creators high up the Substack politics chart:

Which brings me back to the downsides of this immediacy, this disinhibition. “I don’t think my writing suffers much from not being in a newsroom,” Rowley tells me. “I’ve always been pretty hot on typos. But I do think my writing would be much, much worse if I hadn’t worked in a newsroom for more than a decade before setting up my Substack. In the broadest terms, the Telegraph taught me what a story is and The Economist taught me how to write one clearly and concisely. Without either bits of training, my Substack would be poorer.” [Something grammatically off here but as in quote I suppose fine to leave? Sorry Tom!]

But those skills – story finding a story and and writing it up with clarity and precision – are hard to sustain in this era. Substacks are often guilty (and I would be sentenced to life, without parole) of criminal excessive verbosity (I would be sentenced to life, without parole), in just the same way that podcasts have taken the finely-honed traditions of talk radio and stretched them into a rambling, discursive and frequently nightmarish format. Philippa Perry, a psychotherapist, author and Guardian columnist, posted on Substack that “someone has told me my posts don’t appear to be proofread”. Rather than being chastened by this, Perry responded to her inquisitor: “She’s dead right! They’re not… I tried AI as a proofreader but it replaced all normal punctuation with dashes and kept trying to add extra, superfluous, unnecessary adjectives… so apologies for clumsy sentence construction and typos.” Perry is currently listed as having ‘thousands of paid subscribers’.

In my other job, as where I’m a podcast producer, I work with

I’ll never be as hardline as Neil on this, but it’s what’s clear is that we’re bearing witnessing to a deprofessionalisation [Is this knowingly informal? If not "the decline of journalistic standards"?] of journalism. In newsrooms around the world, the impact of cost-cutting falls, first, on the teams who support the top-line [starry? recognisable? public-facing?] journalistic talent. Fact checkers (who make sure the piece holds water), sub-editors (who fine tune the technical writing)†, designers and picture editors (who shape how the piece will look on the page or screen), and editors, who take nurse the writer through multiple drafts to produce the best possible piece outcome. As I write this newsletter, I am reading Graydon Carter’s memoir of his time at Vanity Fair, When the Going was Good. In the 1990s (when the going was, as the title suggests, good) Carter was able to commission serious long-form journalism, with a decadent word rate, giving writers and months, if not years, to research and develop the story. Reading about that era now, it seems feels like an alien culture. Not just because the money isn’t around to keep Christopher Hitchens in cigarettes or Norman Mailer in rum and grapefruits, but because the true locus of journalistic power has shifted, dramatically, from reportage to opinion.

†[In most newsrooms the subs are the fact-checkers, and I'd say something like "who enforce the style guide and scour the piece for factual and grammatical errors"]

Sure, columnists have always been powerful. But their influence, in the past, was tied to the position of the column. That term – ‘column’ – originated in the vertical layout of the type, but it was always an apt name. Columns, after all, held up the ideological structure of a publication. Not the foundations, not the roof, not the facade, but the stanchion that props up the public perception of a title. Now though, opinion has become the whole building. This is the result of a concatenation of aforementioned trends – predominantly the need for low effort, high-yield content and the fetishisation of a form of journalistic celebrity – something that the rise of Substackification has only exacerbated.

Krugman was always prolific. As a rule, he wrote twice a week for the Times. On his Substack – which has over 374,000 subscribers at time of writing – he posts every day (sometimes more than once). I’m unsure whether this cadence is a good thing. He is a hive of industry, but he is also a single intellect (albeit a Nobel prize winning one) with a single perspective. Building Planet Krugman into a mini media empire might be lucrative (Substack labels him as having “Tens of Thousands of Paid Subscribers” at a minimum annual spend of £55, giving him a return of, at the very least, £550,000 per annum [Presumably Substack takes some of this?]) but it cannot offer readers the same breadth of information and tonal variety as is also a far cry, both in revenue and in plurality of content, from the great publications of yore. It raises the question of whether it’s even possible to build a new, yet traditional, media company in this landscape.

There has been, it seems to me, a subtle but important shift in the ambition psychology of media folk. Where people once aspired to create a glossy magazine or produce a news show on cable TV, they now see a direct-to-consumer approach as the the most expeditious route to fame and fortune via a direct-to-consumer approach. After all, Joe Rogan is a household name in America; Ben Smith, founder and editor-in-chief of Semafor, probably couldn’t be picked out a line-up by his own children. Here in the UK, Rory Stewart and Alastair Campbell have cut-through massively with the public as political commentators. Could the same people who religiously tune into The Rest is Politics name the Chief Political Correspondent of Channel 4? (a: Alex Thomson) Sky News? (a: Jon Craig) Or even the BBC? (a: Henry Zeffman). Somehow I doubt it. The reputation of the brand matters far less than the recognition of the journalist. [I feel like some of these examples could have come higher in the piece when you first talked about the cult of the personality journalist and the importance of brands?]

All this would be a toss-up as to its merits or demerits, were it not for the fact that Core journalistic skills are being lost in this great migration. I asked Rowley whether, now that he’s a Substacker as a writer, he’s also become a Substacker as a reader. Or has he retained a bias towards the certainties of legacy media? “100% yes,” he responds. “If I read a fact in The Economist or FT, I think it’s probably true. If I read it elsewhere in old-fashioned media, I think it might well be true. If I read it on Substack, it’s the equivalent of hearing a fact in a university debating society: an interesting nugget buried in an argument or a personal narrative, but not something I’d want to bet on.”

Misinformation (and its evil cousin, disinformation) is rife on all new media platforms. The absence of any hard curation or moderation, the whims of the algorithm, conspire to create an environment of mistrust. Substack has little recourse against publishers who pervert reality, and the nature of the newsletter business – once that email is sent, it’s sent – makes it particularly hard to fact-check get to grips with creators who write false or defamatory pieces. (I contacted Substack’s press office to ask what they were doing to tackle this problem – I did not hear back). It is clear, already, that some people feel like these new media formats have become a breeding ground for thought at the ideological margins, too extreme for mainstream publications. That makes it all the more important that some standards are upheld. [poss cut whole paragraph?]

But this isn’t just liberal pearl-clutching about right-wing nincompoopery [misinformation?], Russian bots, or, frankly, any journalism that isn’t Martha Gellhorn or John Hersey. There is also a genuine, qualitative question about the quality of the work on output via these self-publishing platforms. [That's what you've been saying since the start? Why is it being introduced as a new idea now?] It’s not just typos and wonky facts (after all, 99% of tyops are still leggible). But the act of Journalism is half art, half science. As Krugman noted, in his Substack arrival blog, “if a column didn’t generate a large amount of hate mail, that meant that I had wasted the space.” [Feels like a non-sequiter from previous sentence?] And whilst this might be a fine rule if you’re a venerable economics commentator kept in check by legacy media’s standards of taste and fact-checking, continued to its logical conclusion it creates an ecosystem that rewards big punchy opinions and baseless claims. It pushes people towards the extremes and in the direction of exceptionalism, in a way that the anchoring presence of editorial guidelines avoid. In the several years that I’ve been writing independently on Medium and Substack, my two best performing pieces were headlined ‘2022: The Year That Podcasting Died’ and ‘The End of the Subscription Era is Coming’. Two totally unsubstantiated but effective headlines, which cut through the fractured noise of this self-publishing bunfight.

Throw Artificial Intelligence into the mix (or, to be more precise, pleeeeeease don’t) and you have a genuine degradation of quality. It’s not just the impact that ChatGPT and other LLMs are having on writing (NaNoWriMo, an initiative since 1999 to get people writing more fiction, has already been killed by AI), but on the supporting materials: I can never go on Substack or Medium anymore without being greeted by horrible AI cover art. A generation of illustrators and graphic designers are being put out of work, forced to stack shelves, in favour of a visual aesthetic scraped from the bowels of hell. AI is also being deployed to market newsletters and podcasts, artificially hyping them and gaming the referrals system. And while money is being drained from journalism content businesses – like the last filthy water being freed from the bathtub – money is gushing into AI like an infinity pool at the Burj Al Arab. The asymmetry of this battle, already plain to see, is only going to become more pronounced.

The journalist is a constituent part of journalism, but it is by no means the whole thing. There are undoubtedly some independent publishers who see this and want to build out their offering to inculcate this ethos of teamwork (Lex Roman tells me that writers such as Ryan Broderick and Matt Brown have employed staffers). [cut everything in this para up to here] Not everyone is as enamoured with the ‘hit send first, regret later’ model dynamic of modern publishing as the legions of posting-obsessed social media addicts. There are plenty of people who still favour a more mature, judicious, responsible and sustainable media ecosystem. Publications such as The Free Press and

But Ultimately, though, if the message being put out there is that the media, in its most vibrant form, is being resuscitated on Substack or in podcasts or on a YouTube channel, who is going to disagree? Who would begrudge some journalists finding huge audiences and achieving a big payday, after the tumult of the past two decades? And I certainly don’t blame those people who are making bank from this trend. I can tell you right now, If I was making $500,000 a year from this Substack, I would have far fewer criticisms of the industry shut the f*** up about all this stuff sharpish.

But journalism is a fundamentally contracting sector. Newsrooms will never employ so many copy editors or photographers or courtroom sketchers again. Where do you go to get your start now? Where do you learn the tools of the trade? How do you support the journalistic enterprise if you don’t want to be a writer (believe it or not, some people don’t)? Substack is not the answer for beginners; it is a solution for the fed cats of legacy media who feel squeezed, endangered or disrespected by a shrinking industry. But to feel precarious in a job is very different from feeling like there’s no job for you at all. It won’t take long for the support skills of the journalistic enterprise to die out. Perhaps some can be replaced by automation, but many won’t even be thought of again. We’ll just accept the piecemeal erasure of the standards that have been laid down and codified over the course of 300 years, since the first printers in Germany and France began putting out newspapers at the start of the 17th century. That’s a lot of history, a lot of tradition, to blithely abandon.

The media isn’t dead – they’ve got that part right. But whether it has emigrated to Substack to live, like a 20-year-old nail technician from Chingford touching sand on Bondi Beach, or to die, like a last hurrah in Switzerland††, remains to be seen. One thing is clear: we cannot sacrifice journalism to save the journalist.

††[See what is trying to be done but not quite working for me]

EDITOR’S NOTES: My overall thoughts are that, ironically, it’s much too long. Once you get past mentioning Neil Collins, you go back into the rise of the personality journalist on Substack and other platforms -- isn’t that what the first 1500 words was about? By the end I was finding it all quite circular. If I had a few hours to spend on this I’d restructure and cut at least 1,000 words from it. Think it would help if you broke it up into smaller sections in your mind -- the degradation of standards, the rise of the personality journalist/journalist as brand, etc, rather than returning to all problems throughout. (Also worth flagging the potential irony of stressing the importance of reporting etc in a piece that doesn’t have too much of that and is more like a column written at New Yorker reported essay length!)

As someone who started doing news reporting after being schooled by future bookshop owner Tom Rowley, it pains me to say he's largely right in this piece. Especially on the 'not having an editor is a bit liberating but only if you've already gained the reporting skills from elsewhere' argument.

Substack has a real problem with making NEWS REPORTING work financially and culturally. There is no way that I'd be able to have reported this investigation this week if I hadn't spent years with incredibly experienced editors, lawyers, and data staff at BuzzFeed/Guardian: https://www.londoncentric.media/p/asf-aziz-london-candy-shops-gift-shop-unpaid-tax

News is just an enormously more expensive and time consuming process than comment or columnising, I'm now working six/seven days a week often until midnight and haven't taken more than a couple of days off in the last year. News is highly speculative, as you don't know if a tip you spent weeks on will definitely turn into a post. News is lower reward, as you might get an "important" worthy scoop but people don't really care or want to pay. And as we all know, the news just turns people off in so many ways!

So does Substack want to support NEWS REPORTING as part of its future of the media mix?

I've bent the bosses' ears about this. No, there doesn't seem to be any interest in a a special category on credible news, whether in terms of reduced fees or financial support — although the Substack Defender programme has been a boost in terms of reducing my legal bills. And the risk is that as the Substack app and the feed become the focus of the company and focus more on what a scrolling user wants, will they actually want hard news? The choice of every other platform with a feed suggests not.

tl;dr I think I've built a just-about-financially-sustainable but personally-unsustainable news outlet thanks to Substack and don't know it's really a scaleable model for many others

"I actually was sparing" is priceless