In my younger and more vulnerable days, I was a big Harry Potter fan.

As a bookish kid of precisely the right age, I was somewhat predestined to this role. But I grabbed the opportunity with worrying alacrity. I spent much of my days reading and re-reading the books, and much of my nights on fan forums speculating and exchanging opinions. I even launched my own fansite – Trivia-Duelling.com – to combine my established love of the Potterverse with my incipient predilection towards digital media.

Almost twenty years later, however, and I find myself witnessing the birth of HBO’s Harry Potter TV series (the first time the franchise has come to the small screen) with limited enthusiasm. There was a time, of course, when I would have heartily agreed that each book in the Harry Potter series deserved an 8-10 hour adaptation that cuts no corners. But that was a time when I was a 13-year-old boy who had all sorts of insincere or nonsensical preferences. (And one must never give the cultural whip hand to teenage boys, otherwise you end up with the MCU…). Now, as a reformed Potter fan (I don’t apologise for enjoying them as stories, even if I feel very disconnected from their author), a TV critic and a media analyst, I look ahead to the 2027 release of HBO’s Harry Potter with a sense of weariness.

That lack of enthusiasm was consolidated, this week, when the first production photos emerged. Among them was a snap of 11-year-old Dominic McLaughlin, in the title role, looking uncannily like a pre-pubescent Daniel Radcliffe, and another of Nick Frost as Hagrid, looking like Robbie Coltrane on Ozempic. In fact, both shots were unified by a sense of familiarity. They could easily have been lifted from the movie franchise, which began in 2001 and has run and run since then.

What is the point, you might reasonably ask, of investing a huge amount of time and money into a project that aesthetically rehashes an 8-part movie series that was only completed in 2011? Those movies have barely aged and are still garnering huge (and new) audiences on Netflix and other streaming platforms. Yet industry analysts have speculated that HBO is willing to spend $100m per episode on this series (a striking budget increase on the reported $100-150m spent on each of the feature length movies). It seems plausible, therefore, that HBO will spend $5.6bn on this series, if it runs for its entire, mooted length (assuming 7 seasons of 8 episodes at a cost of $100m per episode), making it one of the most expensive cultural artefacts in human history. And yet, clearly it will be unmistakably similar to another recent, successful and expensive adaptation of the same IP.

But HBO – and Warner Bros Television – have fallen into a trap from which there is no climbing out. The world of Harry Potter began in 1997, with the publication of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone. But in the entertainment age, books are profitable, primarily, as conduits to mass media entertainment, and it wasn’t until the first movie came out, in 2001, that Harry Potter really became a business enterprise. That movie did many things. It elevated the IP to a rarefied level – the sort of position only occupied by a Star War or a Super man – but, equally importantly, it codified an aesthetic. The “look” of the franchise was set in that first movie. The fact that Nick Frost’s Hagrid looks like the Hagrid that appeared in 2001 is not an accident: it’s a continuation of the Potterverse’s distinctive visual profile.

There’s a world in which this trap might have been reversible. Think about the way that franchises like James Bond or Doctor Who have regenerated. Not only does Daniel Craig not look like Roger Moore, Casino Royale doesn’t feel much like Moonraker. There has been scope, in that world, to tinker round the edges. But in the years since 2001, Harry Potter and Warner Bros have doubled-down on the Wizarding World as it was built out by legendary production designer Stuart Craig and costume designer Judianna Makovsky (who would go on to play the same role for The Hunger Games, another franchise trapped in a similar, but far smaller, cycle). When HBO announced its Harry Potter series, it was accompanied by a shot of Hogwarts – the magical school from the series – composed exactly how it appeared in the films. Even the buildings, hardly the most important element in the storytelling, are unchanged in 24 years.

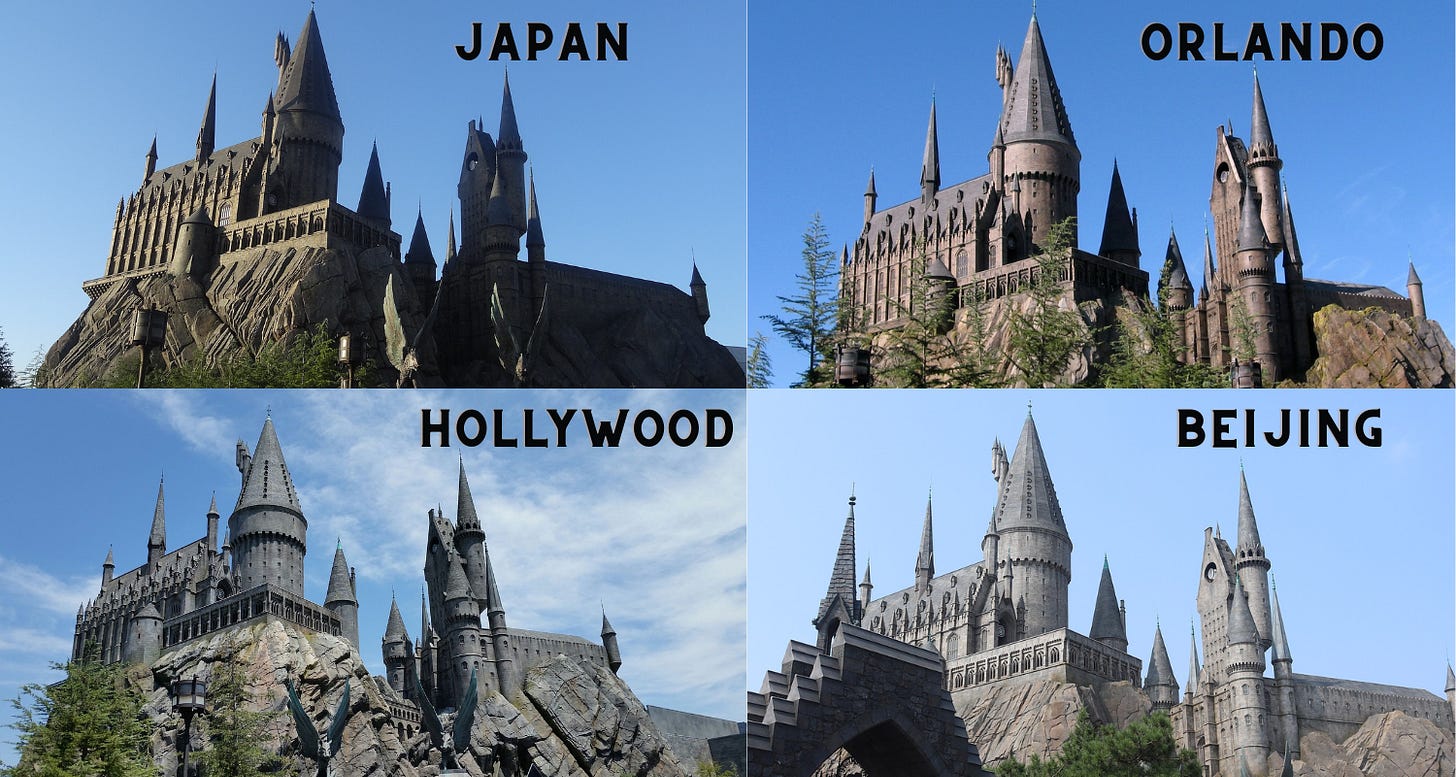

But this is because Warner Bros has backed Harry Potter so heavily as a visual product. Prime among those investments is the theme park at Universal Studios in Florida, which opened in 2010 and has since been accompanied by spin-offs in Hollywood, Osaka and Beijing. All are structured around the same basic experience – a simulator ride through Hogwarts castle – which has necessitated the building of a scale replica Hogwarts on each site. And naturally, all of these castles, all around the world, have to look the same as the castle in the movies, in order to satisfy their visitors expectations of what Hogwarts looks like.

This is something quite novel to the experience of IP development. The Harry Potter Industry is now wedded to a massive, global infrastructure development. When Portkey Games, the company which now handles the Harry Potter IP for video game development, launched its first game – Hogwarts Legacy – in 2023, it was inevitable that the layout of the castle would mirror the films and theme parks, even if the open world nature of a game meant they weren’t inhibited in the way that linear programming is. That game is a particularly interesting case study, as, in order to try and create a new IP pathway, it is actually set in 1890, a 100 years before Harry Potter goes off to school. Yet, visually, the game is instantly recognisable as part of the Potterverse.

Fundamentally, though, being derivative of oneself is no big deal, so long as the IP is progressing. After all, every Star Wars movie is governed by a similar aesthetic, even if there’s been more natural innovation between George Lucas’s first space opera in 1977 and the more recent outings. Consistency is, in many ways, key. We have seen the struggles of DC Comics, who have failed to nail down a tone that runs across their oeuvre, from the moody Christopher Nolan Batman films, to the bubblegum anarchy of James Gunn’s Suicide Squad. They have been in the shadow of their biggest competitor – Marvel – precisely because they have been inconsistent, not just in terms of quality but with regards to their approach.

No, the Harry Potter TV show feels more egregious because it is a direct retread of ground that has been recently trammelled. When Gus Van Sant decided – for some reason – to do a shot-for-shot remake of Psycho, there was natural ambivalence from cinema goers. But at least that project was separated from its forebear by a gulf of 38 years. Running for 104 minutes and costing $60m, it was a bearable experiment for both audiences and Universal Pictures, even if it ultimately bombed at the Box Office. But how would it have fared if Hitchcock’s tight thriller had been stretched out over a 10-episode series?

It’s impossible to know precisely, but when, in 2013, screenwriter Robert Bloch decided to expand the Psycho universe for television, it’s telling that he, and A&E, developed a prequel. Bates Motel took visual motifs from Psycho, as well as developing the all-important mother-son dynamic, but it wound the clock back, expanded the world and drew out fresh, new characters. This is the sane approach. But HBO have gambled on the fact that the Harry Potter IP has performed best when it has remained close to that core idea: boy wizard attends magic school and repeatedly saves the world. That was a huge hit for the books, a mega smash in movie format, a blockbuster video game franchise, and now, according to HBO’s estimation, the biggest TV show proposition the world over. Compare that to the Fantastic Beasts films, which were set in the same universe but with an almost entirely new cast of characters and set of locations, which flopped and were put out of their misery with the franchise still incomplete.

And so, the trap is also the safest bet. Keep the IP as similar as possible and just keep re-selling it. This worked for the opioids industry, so why not for entertainment?

But the Harry Potter Trap is also a further warning about where our entertainment culture is going. Broadcasters don’t want to make expensive bets if there’s unmanageable risk. This is why we’ve seen IP being rehashed and milked with increased single-mindedness. (Only 1 of the top 10 movies this year at the US Box Office is an original property, and that feels like a remarkable over-representation on normality). Audiences, too, seem content with rewatch culture. That’s an essential part of HBO’s bet: after 25 years, the Harry Potter movies are still being watched, over and over, by their original audiences, as well as new ones. With that appetite for the original product still there, it’s a safe assumption that they’ll have a hunger for the new series. Indifference to Fantastic Beasts was accompanied by a continued reverence for the original 8-movie saga: the learning is clearly that reinventing the wheel only results in a rickety car.

Above all else, everything I’ve written here is screamingly obvious. Nobody at HBO is scratching their head and wondering “is our Harry Potter going to be different enough?”. This is because culture, generally, has a dangerous lack of self-confidence at the moment. HBO, who have been a bastion of great TV shows, from Sex and the City to The Sopranos, seem to have lost faith in their ability to pick a winner. Their big shows of the last couple of years – House of the Dragon and The Last of Us – have been adaptations with baked in audiences. Critical and awards darlings like Succession have not proven a particularly effective mass-mover of subscribers. And so, HBO and Warner Bros and LucasFilm and Marvel Studios and DC Comics are willingly lowering themselves into the trap, not because they want to create good art, but because they want to survive. Down in the trap they are safe from the currents impacting the surface world, but what kind of life is it in a hole full of decomposing rats and piles of excrement?

Yet I still think there’s a chance that audiences will repudiate HBO’s thesis. They will find the Harry Potter TV show an indulgence too far. “We were happy with the films,” they might well say. “Why would we want them even longer, and with none of our favourite actors?” In the end, the failure to resurrect the ghost of Alan Rickman might be the doom of this project. And if that assumption sputters, then the whole basis of this low-risk cultural output starts to look shaky. I won’t put money on it, but I’ve got a sneaky suspicion that a $5bn Harry Potter TV show might not look like a very savvy outlay in a few years time.