It's Time to End our Subscription Addiction

Can the media survive the inevitable horrors of 2025?

There was a time, not that long ago, when the funniest writing in the world was happening on Twitter. And the undisputed philosopher-king among Twitter shit-posters was an account called dril. It is said, amongst my friends, that there’s a dril quote for everything, and I’d like to use one as an epigraph for this piece:

“Food $200 Data $150 Rent $800 Candles $3,600 Utility $150 someone who is good at the economy please help me budget this. my family is dying”

The joke is, obviously, that one shouldn’t spend $3,600 on candles. Those candles are too expensive – or you’re buying too many of them. But really, from an “economy” perspective, the issue is not the outgoing on candles but the relative cost compared to, say, rent. Spending almost 5 times as much on candles as rent seems a sufficiently absurd idea that we recognise it, immediately, as a joke. If someone was renting a $40,000 pcm apartment overlooking Hyde Park, would I be so shocked that they’re also spending $4k on candles? Not at all. The joke there would be quite different – the joke would be on us.

But how much should we spend on candles?

This is, I think, the most important question facing the entertainment industry, and broader media landscape, right now. The candles are – if it’s not apparent already – a metaphor. They represent life’s luxuries, big and small. Food, rent, utilities: these are unavoidable expenditures. Streaming platforms, video games, restaurants, football season tickets, craft beer, porn, Ubers home at 3am, artisan sourdough deliveries, the latest iPhone, a gold ornamental dolphin, new clothes in the sales, new clothes not in the sales (but really great value, I promise!), and, yes, a patchouli and sandalwood scented candle: these are life’s avoidable, but delicious, expenditures.

There has been much talk, throughout 2024, about the cost of living. Rising inflation has been a staggeringly effective force for change throughout the world: no major election in 2024 was won by the incumbent. Here in the UK, the Tories were swept aside by the cost of salad; in the US, it’s clear that inflation at the gas pump Trumped the, very real, economic progress of the Biden administration. But what I want to discuss today (so settle down children, get yourself a snack and a fizzy water) is less the rising cost of everything, but the rising everyness of cost. (That is a very fun but confusing way of expressing: things that used to be free now cost money. Things that used to be bundled into a single fee are now spread into several. Candles, candles, candles.) There’s probably a term in real economics for this (it’s not dissimilar to shrinkflation), but, on the off chance there isn’t, I’ll take a stab at a coinage: spreadflation.

In the summer of 2023, I wrote a piece called ‘The End of the Subscription Era is Coming’. The central thesis of this was that the rise of separate subscriptions for things like entertainment and journalism was unsustainable. The overall costs of these things were rising too steeply, even if atomised subscriptions seemed to reduce waste. That piece has been read hundreds of thousands of times and has clearly resonated with people. Most of all, I suspect, it’s resonated with solo publishers who have felt themselves to be the casualties of this trend.

Put very simply: Jeremy Normalbloke is the writer of The Normalbloke Manifesto, a newsletter that’s been running for several years. In the early days of Substack, he moved over to the platform because it was easy to use and growing fast. Within a year on Substack The Normalbloke Manifesto had 10,000 subscribers, of whom 320 paid £10 a month for premium access, giving Jeremy a pre-tax revenue stream of £38,400 a year. Jeremy was delighted: he could finally earn a living writing, without being answerable to anyone. His newsletter had a solid base and, presumably, he would continue to add subscribers at a faster rate than he’d lose them.

But two things happened in the past couple of years to disrupt Jeremy’s cashflow. The first is that more publications and journalists introduced hard paywalls for their content. This meant that Jeremy’s readers were now having to make an active choice about what they subscribe to. Could they afford to spend £10 on The Normalbloke Manifesto, a bi-weekly email, when they also had to spend $25 a month for the New York Times? Plus, when Jeremy launched TNM, his subscribers, on average, signed-up to 2.5 Substacks. Now, that average has risen to 10. It is not just the accumulating costs that are bothering Jeremy, but the engagement. Open rates are falling, even as total subscriber figure edge up, as are shares. If people don’t read his work, are they really going to migrate to the premium version? And so, as 2025 looms, Jeremy is worried that making an income solely from The Normalbloke Manifesto is no longer sustainable. He know that 35% of his 320 paid subscribers joined with a special New Year offer he runs, and so he’s aware that, by the end of January, that figure could be significantly reduced. Will they renew their subscriptions? Or will they spend their money, and attention, elsewhere?

This is a fictional example. Jeremy is actually in rude financial health, as it is very cheap to be imaginary right now. But I suspect it will resonate with a lot of people, not just on Substack but across the media. Podcasters, YouTubers, social creators, freelance journalists, OnlyFans models, indie musicians, video game streamers, whoever.

18 months ago, I said that the subscription era was bound to face its limitations sooner or later. “The inflection point is coming,” I wrote, “When creators realise the dream of financial success and celebrity is sputtering, so too will the impression that this is a radical new future for content creation fade.” And yet, since then, the subscription era has not ended. Has not even, really, been challenged. In point of fact, a number of things have happened to consolidate the hegemony of the subscription model, and make more acute its issues for independent creators.

One of the biggest of these has been Elon Musk’s desecration of the website formerly known as Twitter. You may think whatever you like of Elon Musk as a businessman and technological innovator – and the continued success of SpaceX and Tesla is commendation enough – but he has run Twitter/X into the ground. This has had many corollary results, one of which is the creation of a digital refugee class amongst online liberals. Much ink has been spilled on the success of Bluesky (I remain to be convinced that it is much more than a talking shop for journos and academics), but the biggest beneficiary, probably, is Substack. The migration from X to Substack has been quick and vast. Writers who had been exhibiting their work on Twitter for a decade have started a Substack account and – hey, why not? – launched a little publication and – yeah, I guess there’s no reason not to – introduced a small subscription tier. It has fundamentally changed what Substack is, from a publisher focused platform to a mixed creator-audience one.

Musk’s Twitter also exposes another online trend that is entrenching the subscription era: platform stickability. If there is one thing that seems to obsess the bods at X – and, to be fair, Meta, Google etc – it’s the idea of getting people to stay on-platform for longer. This is a subject that I want to write properly on, but let’s focus, for now, on its impacts. Twitter (as was) is now prioritising longer form content: longer written posts and, particularly, longer videos. TikTok has, in the past year or so, increased the maximum upload time to 60 minutes (or 10 minutes when recorded in-app). Micro-blogging has become blogging; short-form video has become video.

But how does this impact our subscription addiction? Put simply, it’s a drag on the ability of media organisations to do journalism. Almost every publication and writer has, for some years, been using social media. Over the past couple of years they’ve noticed a de-prioritisation of links. In essence, the ‘algorithm’ (by which I mean, the executive level decision makers) are privileging content where people remain in-app over content that takes them elsewhere. This has had a huge, ginormous, massively under-reported impact on the great metric of digital success: traffic.

Traffic has been the dominant way of assessing media success for some time, and its importance harks back to what is sometimes referred to as ‘the original sin of the internet era’. (Side note: I can never find a citation for this, but I’d like one as it’s a great point, and one I often publicly agree with). The original sin of the internet era, it is said, was to make it free. That freeness allowed it to grow like topsy, to hook not just the youthful generations, but every living generation, on information and entertainment at our fingertips. The question of how the internet would become profitable was a question for sometime in the future. And then the future arrived and, with a careless shrug, a bunch of media moguls said “um, I dunno, maybe advertising?”

Advertising is a staggeringly inefficient method of revenue generation. It essentially involves the careful crafting of a sellable product, and then not selling it but, instead, using it to push other (often less carefully crafted) sellable products. Stop and think, for a moment, about the idea of commissioning a journalist to write a long feature on, say, the fact that “tenderstem” broccoli is a licensed trademark owned by a Japanese seed company. That piece is then edited, sub-edited and factchecked, enhanced with illustrations by a printmaker famous for vegetable designs, and then published online. And, crudely embedded in the middle of the piece, is an advert for drop-shipped Stanley cups for teenage girls.

We didn’t make people pay for journalism when the internet was in its infancy, and now, as it enters maturity, nobody knows the value of anything. We are trying to retrofit direct sales into the industry – that’s what the subscription era is all about – and it’s confusing as hell. We got hooked on an unlimited stream of free media – an all you can eat buffet of stir-fried Tenderstem® broccoli – and now we’re paying the price. And so, in the absence of direct exchange of money for goods, digital advertising was asked to carry the weight of funding our media addiction, which meant that ‘traffic’ became King of the Metrics. And in the court of King Traffic I, social media was Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick: kingmaker.

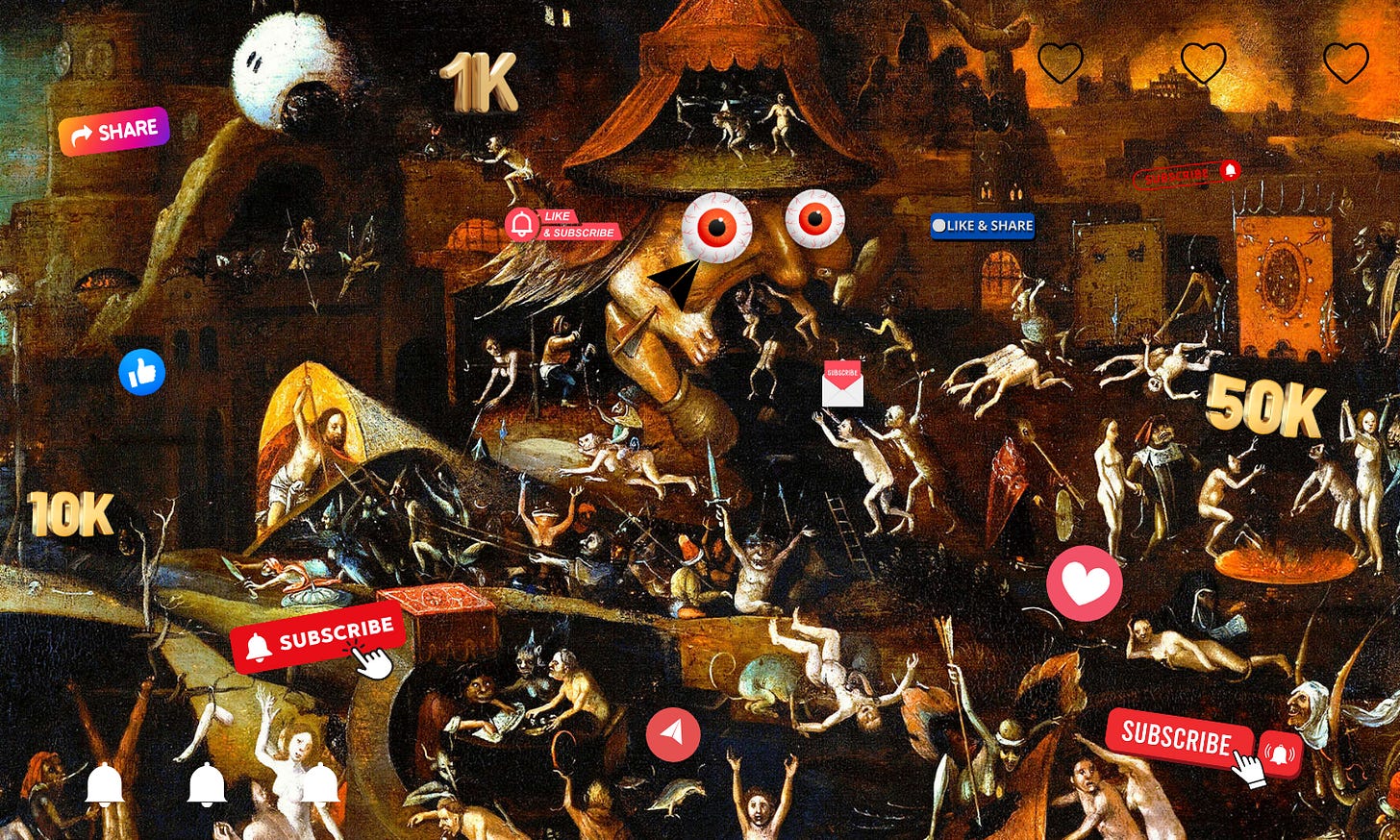

Social media could make or break a publication and an author. People were routinely commissioned on the strength of their Twitter following. That sacred number came up in job interviews, in negotiations for book deals. It became a psychological sickness at the heart of journalism – an addict’s craving for affirmative dopamine rushes that was also, perversely, really professionally important. That hasn’t unravelled fully: whether it’s Twitter or Bluesky or TikTok or Substack, there’s still a number and that number is still valuable. But most of these platforms are now in competition with the publishers they were previously co-existing with. Symbiosis has given way to amensalism.

The doom of traffic has meant that almost the entire media industry has had to move away from digital advertising and towards a hard-paywall. I meet few people, who don’t work in digital advertising, who have anything positive to say about the future of digital advertising. More hard-paywalls mean more subscriptions. More subscriptions means a higher expenditure on media consumption. And that all builds towards this sense of spreadflation.

What is a normal media diet? Jeremy Normalbloke, when he’s not publishing his newsletter, is, helpfully, a completely average guy. He has pretty standard interests (he likes films, TV, fly fishing), political views (he’s a moderate, whatever that means) and has the high-end of average education and income. He is, basically, the man the whole of the media is targeting. He subscribes to Netflix and has done for years, but has also introduced Amazon Prime, because of the delivery extras, and Disney+, for the kids. He has a Spotify family plan and Audible for dog-walking self-improvement. He subscribes to the New York Times, for the puzzles, and the Financial Times, because his parents think it’s good for him. He subscribes to three Substacks: one about fly fishing, and two out of a sense of social obligation to friends. He has a subscription to PlayStation Plus, so he can game with overseas friends, and his son has forced him to take out a Fortnite Crew subscription. He also, though this is put through on his secret Monzo account, pays for two OnlyFans models, not because he finds them sexy but because they “seem like really nice girls and also really smart.”

So what does this cost Jeremy? Mercifully, he lives in the UK, so I can find the details pretty quickly (I have used average monthly costs for both Substack and OnlyFans). The current exchange rate of GBP to USD is 1:1.25.

Monthly costs: Netflix (£17.99), Amazon Prime (£8.99), Disney+ (£12.99), Spotify (£11.99), Audible (£7.99), New York Times online (£8), Financial Times (£39), Substacks (3 x £5), Playstation Plus Premium (£13.49), Fortnite Crew (£9.99), OnlyFans (2 x £7). Total spend: £159.43. (please help me budget this. my family is dying).

Essentially, Jeremy is spending £2,000 a year on subscription media. That’s without things like cinema or concert tickets, books or magazines or newspapers, PPVs from these “really smart girls who are saving up for night school”. It’s a subscription basis that requires him to spend £70 on the latest video game, so that he can use his network capabilities, or £200 on Bang & Olufsen headphones so that he can really immerse himself in high-fidelity streaming of the new Billie Eilish album. And Jeremy is just a normal consumer: some people are trying to maintain 30 Substack subscriptions. Some people feel like they need NowTV and AppleTV+ and Paramount Plus and HBO Max and DAZN and Hayu and Hulu and Rakuten as well as Netflix, Amazon and Disney+. And Jeremy is, most importantly, not interested in football, otherwise he’d need the Sky (£35) and TNT (£30) sports packages.

No, it’s quite clear that consumers are being screwed. The subscription era has peddled, in unholy tandem, along with the licensing era, which is even more pernicious. Back in the good old days, I could buy a copy of Microsoft Word and that would be mine, forever. Now I buy a “license” to run Microsoft Word on my MacBook (AppleCare: £34.99 per year) and Microsoft charges me £5.99 a month for that privilege. The same is true, essentially, of all the software I might reasonably use: Adobe, Logic Pro, Canva, Hindenberg, whatever. I don’t really own anything, anymore, I just rent the right to use it for a while.

Downstream of consumers being screwed (after all, consumers have to be at least partially screwed in order for the great engine of capitalism to keep running) are the content creators, also being screwed.

There is a temptation, always, to bear witness to a gold rush. Elon Musk has repeatedly told his followers on X that they are the media now, and much has been made of the munificence of his new partner programme (though I have yet to see any clear, broken-down reports on earnings). All the same, just look at the publications he actually interacts with. Take, for example, The Babylon Bee, a conservative satire site that Musk restored to Twitter following their 2022 ban. Musk regularly interacts with them, retweets their content and has been interviewed on the site. Yet, when I go on their website I am immediately greeted with a pop-up that yells: “Get a Babylon Bee subscription today to watch our new movie!”. When I dismiss the pop-up I can see that it was hiding a button saying ‘join’. It costs $6-12 a month to ‘join’ the Babylon Bee. And then there’s also a ‘shop’ where I can buy a ‘FAKE NEWS’ hoodie for just £40. I log-off, instead.

Even though I personally don’t care about the fundraising travails of The Babylon Bee, it is typical of a simple fact: it doesn’t matter how much you lick the boots of the Big Tech establishment, there is no getting away from the brutal realities of the subscription era. Revenue sources are not simple. Just look at X itself, which has just sent me a push notification begging me to take out a premium subscription. (They are, themselves, a fascinating example of a correct thesis – digital advertising is doomed – coupled with a horrific solution – alienate all digital advertisers and then push subscription access to the remaining hellscape). This subscription obsession positions access over ownership, and if consumers never have something tangible to hold onto, then the ability is always there to spread and spread and spread. Before, if you wanted to own three films – Monster, Monster’s Ball, and Monsters, Inc, say – you would buy three DVDs and you’d have them forever. Now you’ll need a bunch of different streaming services to pin down rotating libraries and complex IP deals. You can never truly own Monster, Monster’s Ball and Monsters, Inc anymore (unless you already have them on DVD, in which case, you’re sorted).

So, how do we decouple from subscription addiction?

Last time I wrote about the evils of the subscription era, my post ended up on the r/irony sub-Reddit. I was, after all, saying how bad subscription fanaticism was while, at the same time, encouraging people to pay for my work. I’m not one to criticise random Redditors, but I don’t think there’s any real irony there. For better or worse, I find myself writing independently about the media industry. And that means that I have to find ways of generating revenue. I don’t think that subscriptions are bad things, in and of themselves. Paying for stuff that you enjoy is really important – and, as previously said, I am fully onboard with the idea that the antediluvian failings of the dot-com era stem from an absence of direct pricing on Day One. I encourage people to take out a paid subscription whilst being quite ambivalent about whether they actually do.

That’s a luxury not available to most Substackers. Most of the people who write, seriously and regularly, on this platform, would like to make their living through it. So while I might want to tell people they should go cold turkey on subscriptions, I’m also keen to emphasise that it would be good – great even – if you took out more subscriptions. Pay for more journalism, pay for more movies, pay for more TV, pay for more books. That sounds great to me.

At the same time, I feel it is sensible to assume that people have a finite budget for candles. help me budget this. my family is dying. And the media industry – whether that’s hulking great legacy media properties, like the BBC, CNN or News Corp, or insurgents and independents – relies upon some sense of sustainability. The subscription economy does not produce a cashflow more fickle or variable than advertising, but it’s an extremely vulnerable one. After all, there are no six month break clauses here: if you unsubscribe from Future Proof today, you won’t be billed again. That means revenue can be turned off, like a tap.

In order for the media to feel confidence in the long-term viability of its position, more has to be done to ensure that spreadflation doesn’t reach that critical inflection point. The working assumption for the past decade seems to be that a combination of greed and inertia will result in consumers stockpiling subscriptions, building them up and up, and not playing them off against one another. But there comes a point when that changes. Over the course of 2024, the focus on ‘cost of living’ has defenestrated a dozen governments. People in supermarkets were making very real choices: own brand yoghurt (£1.20) or swish probiotic yoghurt from the telly (£3.80). Inflation was such a punchy political tool for a simple reason: people were looking at those prices every day. I see the price on the petrol pump go up, the cost of milk increase, the quotes for my car insurance go through the roof. The slow agglomeration of subscriptions is something that happens, largely, out of sight and thus, largely, out of mind.

But people are not total maniacs. The first thing I do if I feel any financial pressure is cancel my decadent Beer52 subscription. And if regular people are spending £200 a month on media subscriptions, there will eventually come a point where belt-tightening impacts that bundle. It is not possible for hundreds of different services that used to be free to suddenly all become expensive and profitable. Similarly, it is not possible for journalists who are finding themselves victims of hiring freezes or creeping salary cuts at traditional publications to all suddenly find themselves launching expensive and profitable newsletters. Not all podcasts can be expensive and profitable, not all videos can be expensive and profitable, not all porn can be expensive and profitable.

Spreadflation is just inflation by another mechanism. Assume, then, that like the price of petrol at the pump, a sense of rationality will return to the market. In the UK last year (2023), the average household disposable income was £34,500. That’s total income after direct taxes (National Insurance, plus income and council tax). The average rental cost of a 4-bed home, outside London where it’s more expensive, is about £1,325 pcm or £15,900 per annum. The average household energy cost last year was £1,717, whilst water was about £500. That means that £19,442 of that £34,500 has, on average, evaporated before we even talk about things like wi-fi, data plans, car insurance (plus road tax), savings, or, you know, food. The average UK household spends £63.50 a week on food, which is £3,175. Petrol, dog kibble, clothes, childcare(!), prescriptions, home maintenance and improvement, private pension contributions, holidays, the list goes on. And after all that, people are expected to stump up a baseline £2,000 to be an average consumer of completely average media?

It’s all a bit insane. Even though it was designed to reduce the cost-to-consumer of the unread portions of the newspaper, or unwatched channels of the TV, there’s too much waste in the subscription economy for it to be sustainable. People are not purchasing what they need but a prediction of what they’ll want, and a guess at what they’ll get. It is a vicious circle, where atomisation begets more atomisation. It made sense for Disney to launch its own streaming service, rather than licensing its content to different providers, but because of that, it makes sense for Apple to do the same. And Paramount. And Lionsgate. And so on.

But the streaming industry should offer some hope that sanity is reasserting itself. Apple, which has been a very slow mover in this space, has recently made its content available for purchase via Amazon Prime, a recognition that it is a luxury streamer and not a core one. Indeed, Amazon is starting to reposition as a marketplace rather than a library (almost like a big online supermarket…hmm…), allowing them to keep costs down. I wouldn’t be particularly surprised if Amazon Prime phased itself out of the subscription streaming game in the next few years. Nobody understands the power of direct sales quite like Jeffrey Preston Bezos. (Paramount+ and Lionsgate Plus are both already available via Amazon).

But what does that mean for folk like Jeremy Normalbloke? After all, he is subject to the macro currents but can do little to influence them. For me, there is a magic number here. Assume that, in the English-speaking world, only about 25-50% of the population would ever pay to subscribe to a newsletter or podcast. These are the people I’m talking about. I reckon, based on fag packet calculations, that the magic number is about $250 a month, spent on subscription media, before people start to look at that shopping list a bit more closely. And so Jeremy can either ensure that The Normalbloke Manifesto is part of that $250 (either by increasing its quality or decreasing its price) or he can look for other revenue sources. And therein lies the greatest challenge in all this, because the media is a shrinking industry. Journalism is worst affected, but the entertainment industrial complex which expanded, like the ripe belly of Violet Beauregarde, is also in the throes of a contraction. Demand for mid-range, mid-quality content has never been lower in the modern era. The whip hand has been offered to wildly expensive action movie sequels or, conversely, inane crapola of a denominator lower than the lowest (usually featuring a YouTuber burying himself alive, for some reason).

And so, as 2025 begins, I’m keeping two dangers front of mind. Firstly, that the backlash to spreadflation will culminate in a reduction or stagnation (which will, in real terms, feel like a reduction) of payments for content. But also that with content easier than ever to create and distribute, we have to be conscious of meeting demand rather than exceeding it. A surplus will only drive prices down, where there are prices to be driven down. More likely, it will flood the market with free content just at the point that consumers are becoming more aware of the cost implications. And that is a delicate balance.

I want to live in a world where consumers think that $200 a month is a reasonable amount to pay for the media they consume. But if I were told, tomorrow, that the World Government™ sponsored by Tenderstem® Broccoli was introducing a $200 a month tax on fresh air, I would be appalled. Do I believe that fresh air is worth $200 a month? Of course. Would I be happy to pay $200 a month for fresh air? Absolutely not. The value is clear, the price is not.

The subscription era is, in many ways, an answer to the problems of digital advertising, but one that suffers from many of its shortfalls. The challenges facing publishers will become more pronounced in the next year as economic woes dovetail with content reorganisation and AI trashflow. It’s a scary prospect, but if you’re sensible – as a creator or consumer – you’ll start preparing now for a world beyond the heedless subscription accumulation that we’ve relied on so far.

That all said, please do like and subscribe to this.

Behold! We believe that many of the subscription substackers will find a solution in conglomeration. One interesting author for $5/month is a careful consideration, especially given the vast number of interesting authors on Substack. $10/month for a combination of 4 - 8 interesting authors is an easier buy, and we would expect it would significantly increase the number of subscribers, representing significant increase in revenue for all of the authors in the conglomerate.

Substack would be wise to pursue functionality to make such a conglomeration easier.

Reminder, for comparison: a digital subscription to the NYT can be had for ~$4.30/month

oh, god