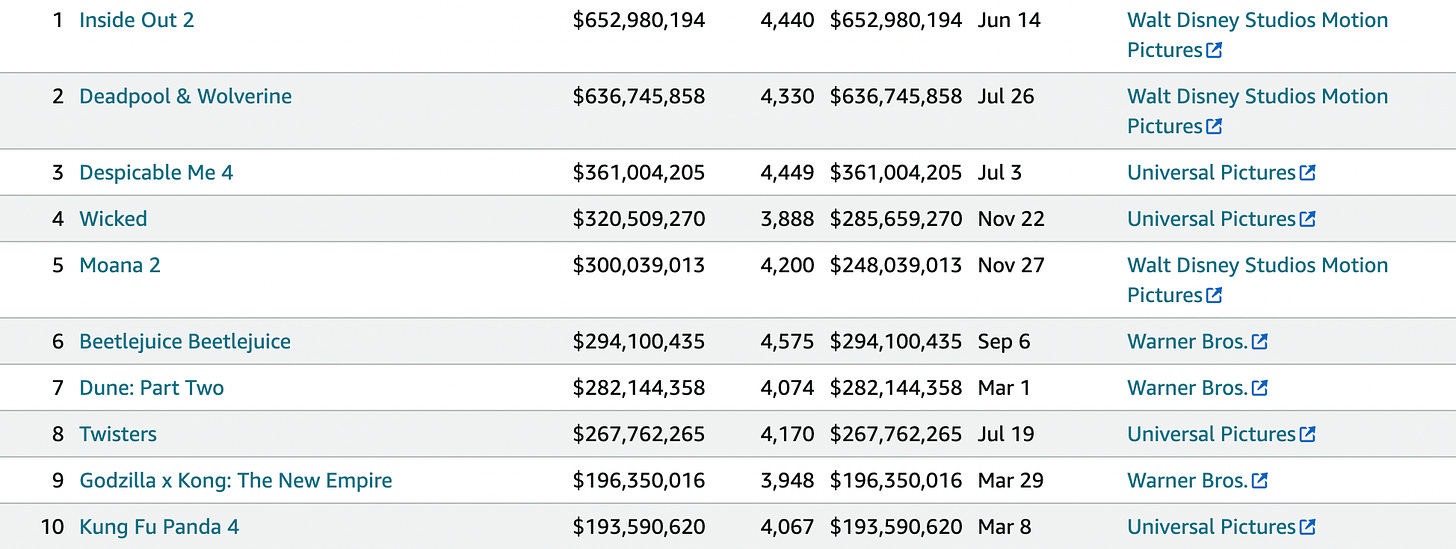

This week, people on social media began to notice something interesting (and scary). All of the top ten movies of 2024, they noted, were sequels. “This is what cultural stagnation looks like,” journalist Ted Gioia wrote. “Everything is reheated leftovers.”

Indeed, while refining the list to a Top 10 made for a neat tweet, the next two on the list – Bad Boys: Ride or Die and Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes – were also sequels. The highest-grossing non-sequel of the year was It Ends With Us, based on the enormously popular book by Colleen Hoover. (Indeed, the highest-grossing piece of genuinely new IP this year was John Krasinski’s IF, which ranked at number 19 and took roughly $111m at the domestic box office). So while people were – rightly – shocked by the absence of non-sequels in the top 10, they might be even more shocked if they knew how deep the rot goes.

(Of course, this all relies on the definition of Wicked – still a big hit in cinemas and likely to move up into 3rd place, before being knocked back down into 4th by Moana 2 – as a sequel. It is a sort-of prequel to The Wizard of Oz, so allowable for the sake of proving a point.)

Now, as we come to the end of another year, it’s worth asking whether a) the Box Office is still a relevant marker of entertainment industry success, and b) whether we have entered a phase of cultural stagnation? (And – spoiler alert – if the answer to b) is ‘yes’, what that really means).

The first thing to do, I think, is to properly interrogate the proposition. Ok, so a lot of the top movies in 2024 were sequels. But how different was this last year? Answer: 5 of the top 10 of 2023 were direct sequels, while 3 others (Barbie, Super Mario Bros, The Little Mermaid) were based on existing IP. How different did the box office look 10 years ago? Answer: 5 of the top 10 in 2014 were direct sequels, another 4 (Guardians of the Galaxy, The Lego Movie, Maleficent, Dawn of the Planet of the Apes) were based on existing IP. Let’s go back another 10 years (why not, I’ve got time on my hands). Answer: 4 of the top 10 in 2004 were direct sequels, while another, The Passion of the Christ, was based on existing IP (ha ha).

But let’s look at the 5 films in 2004 that were neither sequels nor IP derivatives. Pixar’s The Incredibles, which was released during the studio’s flawless run and is a pastiche of the superhero genre. The Day After Tomorrow, a big climatic disaster film. Shark Tale, a crapola Dreamworks rip-off of Finding Nemo. The Polar Express, an ungodly motion capture Christmas film. And National Treasure, a dum adventure cashing in on early-00s Da Vinci Code mania. Part of me wants to say that none of these films are especially aspirational (does it really matter if it’s Moana 2 or Shark Tale in the box office Top 10? Wouldn’t we rather have Dune: Part Two than National Treasure?) but the broader point is that stagnation comes in many forms. It comes in the form of stretching titles through the taffy-puller of sequeldom until the returns diminish to such gossamer thin nonsense that audiences reject them. But it also comes in the form of repeating the same formula over and over, using the same stars, the same directors, the same visual milieu, the same ideas.

A more interesting creative difference between 2004 and 2024 is that some of the sequels being made twenty years ago were genuinely good. Shrek 2, the top movie of the year, was better than Shrek. Spiderman 2, the box office runner-up, was a huge step-up from Spiderman. Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban brought in Alfonso Cuarón and is widely seen as the most creatively ambitious of that franchise. Paul Greengrass’s The Bourne Supremacy has an 82% score at Rotten Tomatoes. Compare those to 2024’s sequels: Inside Out 2 (a significant drop-off from the original), another execrable Deadpool movie, low-end of franchise additions for Despicable Me, Moana and Kung Fu Panda. In a way, the question shouldn’t be “should we stop making sequels?” it should be “should we make better sequels?”.

These figures, doing the rounds, were extracted from the American domestic box office, but the international box office looks much the same. The industry is still in recovery from the covid pandemic (or so the PR spin would go). 2020 saw a -81% year-on-year box office return in the US (-77.9% globally) and that’s been a hard trough to get out of. +112% in 2021, +64% in 2022, +21% in 2023. The worry now is that the growth seems to have plateaued: 2024 might just match 2023 but is unlikely to exceed it. It will leave box office receipts at less than 75% of pre-pandemic figures, suggesting that the industry will have to adjust to a ‘new normal’. This means that theater chains are having to cut costs and raise prices, a sort-of industrial stagflation. The narrative of post-covid recovery is masking a decline that is, basically, unsustainable.

That should be the headline on any analysis of theatrical distribution in 2024. But, in creative terms, a bigger issue for me is that forces have conspired to make this a very weak year for cinema as an art form. This sounds pretentious but I think it’s important. Look at the best picture nominees from 2023: Oppenheimer, American Fiction, Anatomy of a Fall, Barbie, The Holdovers, Killers of the Flower Moon, Maestro, Past Lives, Poor Things, The Zone of Interest. This was one of the strongest fields of the 21st century, and it suggested that cinema was reasserting itself after the pandemic (2022’s releases were still transparently inhibited by covid restrictions: Everything Everywhere All at Once is a very iffy winner). The bookies’ favourites for Best Picture this year however – films like Anora, Sing Sing, The Brutalist, Emilia Perez, and Conclave – look far weaker on paper. Wicked, an outsider, has been a strong performer at the box office, but what’s the next highest grossing film with a shot at a Best Picture nomination? Probably Conclave, the 48th highest-grossing film of the year, which has taken about $30m at the US box office (8 of the 10 nominees last year comfortably out-earned that, and Maestro likely would too, if it hadn’t been released concurrently on Netflix).

The SAG/WGA strike has obviously had an impact, as has a reckoning within the shareholder capitalism motivations of the streaming industry. Budgets are being squeezed, projects without a clear route to profitability are being shelved. But prestige projects are in a tricky position: the trend over recent decades has been towards an increasing importance of star power in marketing, while acting salaries have risen and risen. Movies like Anora, now, are small miracles, in that they’re not draining half their budget on a lead who’ll guarantee the film gets booked on a thousand screens. But, generally, the ‘modest prestige picture’ is getting priced out the market. Once you need a star name to conduct a marketing tour, you’re already pushing the film into a position where it needs to earn $20m+ at the domestic box office, irrespective of other budgetary elements. And that becomes a ‘risk’ in a risk averse world.

It doesn’t really matter who is in the Top 10 of the box office at the end of the year. The headline figure for cumulative box office receipts is more important. And I’ve made this point before but I’ll make it again: post-covid, the most important thing for the cinema industry is to reintroduce the habit of cinema attending. Cinemas need patrons to go see half a dozen movies a year, and if that requires Inside Out 2 to engender that practice, so be it. Maybe you go see Deadpool one week and accidentally find yourself watching Queer the next.

But the focus on stagnation elides a different story: decline. In 2023, 130 movies made more than $20m at the US box office; so far in 2024, only 64 films have reached that marker. That should be the figure that shocks both the public and the industry.

Thank you for explaining why every time we decide to go to a movie and open the Flixter app, my husband and I say "there's nothing out that's looks good" We're avid movie goers but this year I've noticed a distinct lack of quality movie selections and many of the ones we have seen are truly terrible sequels like Joker: Folie a Deux. This year I've often wondered what happened to all the good movies and now I know:(

The film industry is going away, because of crime, woke messaging, and that tv tech streaming is on par with most common theater screens. It may survive, but only have a fraction of cultural relavance or profitability.